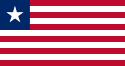

As thousands of soldiers and civilians cheered, 13 ministers and other top officials of the Liberian Government deposed on April 12 were put to death on a beach here today by a firing squad of riflemen and machine gunners. Those shot included former Foreign Minister Cecil C Dennis Jr. and Frank E Tolbert, the presideng officer of the Senate and elder brother of the President, William R Tolbert Jr., who was killed during the coup. Also executed were the speaker of the House of Representatives, the Chief Justice and the chairman of the party that for a century had governed this country, long the closest African friend of the United states.

They had been sentenced to death by a five-man military tribunal that declared them guily of "high treason, rampant corruption and gross violations of human rights." They had been allowed no defense counsel nor had they received any details of the charges against them.

After the executions, a staff sergeant emptied the magazine of his weapon into the bodies, turned to a reporter standing next to hi, and said that those put to death had had "no right to live" because they had made Liberians suffer for years, "Killing people and stealing our money." Reporters were summoned to the beach shortly after attending the first news conference given by Liberia's new leader, Samuel K Doe, the 28-year-old former master sergeant who led the coup of April 12. Anwersing only two of the dozens of prepared questions during the conference, which lasted seven minutes, Mr Doe said he would return Liberia to cicilian rule and call elections "when things have calmed down."

The governing military body, headed by Mr Doe and called the People's Redemption Council, rejected plead from the United States and other Western embassies to spare the prisoners' lives. The 13 Government ministers, legislators, party officials and others condemned to die today were transported by bus to a sandy dune at Monrovia's beachfront Barclay military training base, wehre thousands of civilians and hundreds of soldiers had gathered. Nine thick wooden posts had been lined up along the dune 10 feet apart. The death sentences were carried out in two groups. Nine of the 13 prisoner were first stripped to the waist and tied, one to each post and facing away from the sea. A single long green rope was used.

Soldiers in battle fatigues, mostly armed with submachine guns, milled around the posts jeering at the prisoners who were tied by their waists. It took half an hour for their officer to get them to move far enough back to make room for the firing squad. Mr Tolbert, the Senate president, and Richard A Heneries, the 72-year-old Speaker of the House, apparently fainted, and the firing squad killed them as they sagged to the ground on the rope.

Only the former Foreign Minister Dennis and F Reginald Townsend, former chairman of the long-governing True Whig Party, appeared calm as they faced their executioners. One soldier with a rifle was positioned in from of each post at a distance of 15 yards. As the order was given, each fired several shots. The first shots missed Mr Dennis and some others. The former Foreign Minister appeared astonished. Then other soldiers opened up with bursts of machine-gun fire for several minutes amid wild cheering from the soldiers and from civilians lined up some distance from the beach.

The nine bodies were cut down and left at the foot of the stakes, and the second group of four was brought forward. Moments later, another volley rang out. Besides Mr Dennis, Mr Tolbert, Mr Heneries and Mr Townsend, those put to death today were identified as Joseph Chesson, Justice Minister; James A Pierre, Chief Justice' James T Phillips, Finance Minister; David Franklin Neal, Minister for Economic Planning; Frank Stewart, Budget Director; Cyril Bright, Agricultural Minister; John Sherman, Trade Minister; Charles TO King, a congressional representative, and Clarence Parker, Tru Whig Party treasurer.

Source: New York Times

Tuesday, April 22, 1980

Sunday, April 20, 1980

Free at Last, Zimbabwe Now Must Face Difficult Choices

The Union Jack was lowered at Government House Thursday as the bugler played last post. At midnight, before a cheering crowd, Prince Charles handed over the formal documents of sovereignty. The nation of Zimbabwe was born.

They are familiar ceremonies. Forty-two times, starting with India in 1947, what was once a British territory has become independent but for Commonwealth ties. For both Zimbabwe and Britain, however, last week's events carried more than the usual weight of symbolism. Years of bitterness and death preceded the outcome peacefully celebrated. And much now depends - not only for Zimbabwe but for Britain and the West generally - on whether the new country can overcome that past.

Two basic facts underly Zimbabwe's bloody past and uncertain furture. In population it is an obverwhelmingly black country: about 7 million blacks and 230 000 whites. But white farmers and businessmen and investors created th economy of what used to be Rhodesia - with black labor - and whited held all the economic and political power. After seven years of war and a much longer political struggle, the majority has gained political power. A great question for the future is whether the power can and will be used to sustain the economy.

Robert Mugabe and his government, for example, face an immediate decision on the fundamental matter of food prices. The price of staples was kept low in Rhodesia, for political resons, by the white Government of Ian D Smith and the interim regime of Bishop Abel T Muzorewa. Corn for meal, the most basic item in Southern Africa, still sells here for less than half the price in neighboring Zambia. The subsidy on corn alone is said to cist the Government nearly $40 miilion a year. The hidden economi costs are even greter. With prices held artificially low, tribal villages have realised that it costs them more to grow their food by traditional methods than to buy it. So more and more have gone to townsm to try to fins work and send money home. Five years ago, the large peasant sector of the economy produced more food than it needed. Today it buys a third of what it consumes.

Zimbabwe urgently needs to make its peasant agriculture more productive. But the political cost of letting prices rise to increase productivity would put a burden on the masses who voted the Mugabe Government into office. That is the kind of anguishing choice that will have to be made by the Government again and again. Zimbabwe's advantage is that it is not another desperate third world nation. It has the potential for economic take-off. The country's large white-owned farms boast some of the most productive agriculture in the world, for example. While neighboring Mozambique and Zambia have had to depend on food imports, sometimes coming close to bare cupboards, Rhodesia fed itself. Under the right conditions, Zimbabwe's grain surpluses could help the whole region. As for industry, the world learned during 15 years of trying to supress the white rebellion with sanctions how ingenious Rhodesians could be in supplying their own needs. Andrew Young, in Salisbury las week as a member of the American delegation for the independence celebrations, remarked ironically on the high quality of the workmanship in the modern hotel here the delegates stayed. "if they could build this during sanctions," he said, "maybe they could give us soe advice ..."

Unlike many newly independent countries, Zimbabwe has a reservoir of human skills o which to draw. The white population, small as it is, includes crucial technical and managerial experts. But there is also a black professional and middle class. The country has had an integrated university for years, and there are large numbers of black graduates.

Prime Minister Mugabe has made a particular effort so far to reassure white Zimbaweans and potential investors from abroad. even before independence he emphasized that, though he calls himself a Marxist, he did not want to 'disrupt the economy' by early nationalisation. On the night of independence, he made a moving appeal to blacks to treat white fairly. "It could never be a correct justification," be said, "that because the whites oppressed us yesterday when they had power, the blacks must oppress them today because they have power. An evil remains an evil ... Our majority rule cold easily turn into inhuman rule if we opressed, persecuted or harassed those who do not look or think like the majority of us."

Anothe reasurance to whites, at the moment of independence, was the atmosphere of friendliness between Mr Mugabe and the British Government. In light of history, this was one of the most amazing aspects of an amazing week. The British were humiliatingly powerless when Ian Smith led Rhodesia into unilateral independence in 1965. That was in part because Rhodesia had been a self-governing territory since 1923. The Bristish Prime Minister in 1965 and for years afterward, Harold Wilson, was also singularly unable to marshal effective diplomacy against the Smith regime. The black nationalist movements, including Mr Mugabe's, always suspected that British governments were not so much unable as unwilling to take firm action against their white kith and kin in Rhodesia. The suspicions deepened when a Conservative Government under Margaret Thatcher took office. When Lord Carrigton, the Foreign Secretary, convened the Rhodesian conference in London last fall, Mr Mugabe was highly skeptical. At one point a Mugabe spokesman said the British cease-fire proposals were "a pot fathered by Mrs Thatcher in concubinage with Satan Botha" (Prime Minister PW Botha of South Africa).

The hostility and suspicion carried over into the election run by the British Governor, Lord Soames. Mr Mugabe held out some of his troops, beleiving that the British would deny him the fruits of political victory. There were botter recriminations on both sides about alleged violations of the cease-fire accords. Then, just before the election, the two men met alone together for the first time - and something happened. Aides say each came out of that meeting believing in the other's bona fides. In the days after his sweeping victory, Mr Mugabe sought the Governor's advice, and urged him to stay longer. "I must admit," Mr Mugabe said of Lord Soames in his independence speech, "that I was one of those who originally never trusted him, and yet I have now ended up not only implicitly trusting but fondly loving him as well. He is indeed a great man, through whom it has been possible, within the short period I have been Prime Minister, to organize substantial aid from Britain and other countries."

Robert Mugabe is not looking for Christopher Soames, then, but to the west. That is another reason why Zimbabwe means so much to so many.

Source: New York Times

They are familiar ceremonies. Forty-two times, starting with India in 1947, what was once a British territory has become independent but for Commonwealth ties. For both Zimbabwe and Britain, however, last week's events carried more than the usual weight of symbolism. Years of bitterness and death preceded the outcome peacefully celebrated. And much now depends - not only for Zimbabwe but for Britain and the West generally - on whether the new country can overcome that past.

Two basic facts underly Zimbabwe's bloody past and uncertain furture. In population it is an obverwhelmingly black country: about 7 million blacks and 230 000 whites. But white farmers and businessmen and investors created th economy of what used to be Rhodesia - with black labor - and whited held all the economic and political power. After seven years of war and a much longer political struggle, the majority has gained political power. A great question for the future is whether the power can and will be used to sustain the economy.

Robert Mugabe and his government, for example, face an immediate decision on the fundamental matter of food prices. The price of staples was kept low in Rhodesia, for political resons, by the white Government of Ian D Smith and the interim regime of Bishop Abel T Muzorewa. Corn for meal, the most basic item in Southern Africa, still sells here for less than half the price in neighboring Zambia. The subsidy on corn alone is said to cist the Government nearly $40 miilion a year. The hidden economi costs are even greter. With prices held artificially low, tribal villages have realised that it costs them more to grow their food by traditional methods than to buy it. So more and more have gone to townsm to try to fins work and send money home. Five years ago, the large peasant sector of the economy produced more food than it needed. Today it buys a third of what it consumes.

Zimbabwe urgently needs to make its peasant agriculture more productive. But the political cost of letting prices rise to increase productivity would put a burden on the masses who voted the Mugabe Government into office. That is the kind of anguishing choice that will have to be made by the Government again and again. Zimbabwe's advantage is that it is not another desperate third world nation. It has the potential for economic take-off. The country's large white-owned farms boast some of the most productive agriculture in the world, for example. While neighboring Mozambique and Zambia have had to depend on food imports, sometimes coming close to bare cupboards, Rhodesia fed itself. Under the right conditions, Zimbabwe's grain surpluses could help the whole region. As for industry, the world learned during 15 years of trying to supress the white rebellion with sanctions how ingenious Rhodesians could be in supplying their own needs. Andrew Young, in Salisbury las week as a member of the American delegation for the independence celebrations, remarked ironically on the high quality of the workmanship in the modern hotel here the delegates stayed. "if they could build this during sanctions," he said, "maybe they could give us soe advice ..."

Unlike many newly independent countries, Zimbabwe has a reservoir of human skills o which to draw. The white population, small as it is, includes crucial technical and managerial experts. But there is also a black professional and middle class. The country has had an integrated university for years, and there are large numbers of black graduates.

Prime Minister Mugabe has made a particular effort so far to reassure white Zimbaweans and potential investors from abroad. even before independence he emphasized that, though he calls himself a Marxist, he did not want to 'disrupt the economy' by early nationalisation. On the night of independence, he made a moving appeal to blacks to treat white fairly. "It could never be a correct justification," be said, "that because the whites oppressed us yesterday when they had power, the blacks must oppress them today because they have power. An evil remains an evil ... Our majority rule cold easily turn into inhuman rule if we opressed, persecuted or harassed those who do not look or think like the majority of us."

Anothe reasurance to whites, at the moment of independence, was the atmosphere of friendliness between Mr Mugabe and the British Government. In light of history, this was one of the most amazing aspects of an amazing week. The British were humiliatingly powerless when Ian Smith led Rhodesia into unilateral independence in 1965. That was in part because Rhodesia had been a self-governing territory since 1923. The Bristish Prime Minister in 1965 and for years afterward, Harold Wilson, was also singularly unable to marshal effective diplomacy against the Smith regime. The black nationalist movements, including Mr Mugabe's, always suspected that British governments were not so much unable as unwilling to take firm action against their white kith and kin in Rhodesia. The suspicions deepened when a Conservative Government under Margaret Thatcher took office. When Lord Carrigton, the Foreign Secretary, convened the Rhodesian conference in London last fall, Mr Mugabe was highly skeptical. At one point a Mugabe spokesman said the British cease-fire proposals were "a pot fathered by Mrs Thatcher in concubinage with Satan Botha" (Prime Minister PW Botha of South Africa).

The hostility and suspicion carried over into the election run by the British Governor, Lord Soames. Mr Mugabe held out some of his troops, beleiving that the British would deny him the fruits of political victory. There were botter recriminations on both sides about alleged violations of the cease-fire accords. Then, just before the election, the two men met alone together for the first time - and something happened. Aides say each came out of that meeting believing in the other's bona fides. In the days after his sweeping victory, Mr Mugabe sought the Governor's advice, and urged him to stay longer. "I must admit," Mr Mugabe said of Lord Soames in his independence speech, "that I was one of those who originally never trusted him, and yet I have now ended up not only implicitly trusting but fondly loving him as well. He is indeed a great man, through whom it has been possible, within the short period I have been Prime Minister, to organize substantial aid from Britain and other countries."

Robert Mugabe is not looking for Christopher Soames, then, but to the west. That is another reason why Zimbabwe means so much to so many.

Source: New York Times

Saturday, April 12, 1980

TOLBERT OF LIBERIA IS KILLED IN A COUP LED BY A SERGEANT

Army enlisted men, charging "rampant corruption" in Liberia, staged a predawn coup today in which President William R. Tolbert Jr. was killed and replaced as head of state by a 28-year-old sergeant. In the first announcement over Monrovia Radio after the coup, Master Sgt. Samuel K. Doe said the army would be in charge in this West African counrtyu of 1.7 million people until a decision was made on the government. A later announcement referred to Sergeant Doe as the head of state, which was founded by slaves from the United States as the first black republic in Africa. Visitors to the executive mansion compund said Sergeant Doe was running the country from an outside building, assisted by other enlisted men who referred to him as "Mr. President."

In the Monrovia radio announcement, Sergeant Doe said an Army Redemption Council had seized control because "rampant corruption and continious failure by the Government to effectively handle the ffair of the Liberian people left the enlisted men no alternative." Shooting erupted around the five-story executive mansion, which houses the presidential offices and residence, soon after midnight. There was also sparodic shooting at several military installations.

Sergeant Doe disclosed President Tolbert's death to the Liberian News Agency, but no details were available on exactly how it occurred. Mr Tolbert's wife, Victoria, was arrested, the sergeant said. Sergeant Doe also broadcast announcements appointing junior officers, mostly captains and lieutenants, and some non-commissioned officers to take charge of rural areas. The enlisted men freed leaders of the opposition People's Progress Party, who were jailed after the called March 7 for President Tolbert's resignation. The freed leaders were present at the mansion, but informed sources said they appeared to be acting only in an advisory role.

There was some looting in the capital, much of it by soldiers, with stores owned by Lebanese and Indian merchants and homes of Government officials among the major targets. But the looting was not as widespread as an outbreak last year during rioting over an increase in rice prices. shooting was hears in the capital for hours after the coup, but it apparently came mostly from soldiers firing into the air in celebration. Soldiers commandeered vehicles and rode them through the city. Sergeant Doe proclaimed the situation "under control", but he ordered a dusk-to-dawn curfew and suspended flights to and from the country. He also bradcast order to officials of the deposed Government to report to the executive mansion. The announcements were interspersed with American rock music and African songs.

The 66-year-old slain President was a descendant of freed American slaves who founded the republic in 1847. Though only 5 percent of the population, these "freed-men" have long dominated politics ans commerce, and American cultural influence is evident. Little in known of Sergeant Doe's background, but he is apparently of indigenous origin. "We know nothing about the political views of Sergeant Doe", said the British vice consul, Jeremy Lardner. "we never heard of him before." According to informed sources, however, his political outlook is "moderate".

During the afternoon, the American charge d'Affairs, Julian Walker, met at the executive mansion with Sergeant Doe and invited the Soviet Ambassador to a meeting. The American Ambassador, Robert P Smith, is in the United Stated for medical treatment. Details of the talks were not disclosed but Sergeant Doe appealed to foreign governments over radio not to "interfere". Diplomats here said the coup took them by surprise. Liberia had been regarded as one of Africa's most stable countries. "There was no intimation a coup would take place", Mr Laudner said. "Although one knows such a thing always is possible there was no forewarning".

Mt Tolbert, who was chairman of the Organisation of African Unity, had been President since July 1971 when he succeeded William VS Tubman, who died after almost 28 yers in office. Mr Tolbert was elected to an eight-year term in 1975 and woul have left office in 1983 under a Constitution that limits a president to ine full term. His family has widespread business interests and there have been periodic allegations of conflict of interest and corruption involving Government officials.

The People's Progress Party, which was formed in January, was banned last month after it organised a demonstation at the executive mansion calling for Mr. Tolbert's resignation and a share in political power.

The coup came three days after Amnesty International, a human rights group based in London, charged that the Government had issued "an open invitation to political murder" by offering rewards of $1 500 to $2 000 for the return "dead of alive" of 20 members of the party. The group said in a report: "The 20 proscribed individuals are being sought in connection with a current crackdown on the People's Progressive Party, the first opposition party permitted to function in Liberia since the late 1950's."

Source: New York Times

In the Monrovia radio announcement, Sergeant Doe said an Army Redemption Council had seized control because "rampant corruption and continious failure by the Government to effectively handle the ffair of the Liberian people left the enlisted men no alternative." Shooting erupted around the five-story executive mansion, which houses the presidential offices and residence, soon after midnight. There was also sparodic shooting at several military installations.

Sergeant Doe disclosed President Tolbert's death to the Liberian News Agency, but no details were available on exactly how it occurred. Mr Tolbert's wife, Victoria, was arrested, the sergeant said. Sergeant Doe also broadcast announcements appointing junior officers, mostly captains and lieutenants, and some non-commissioned officers to take charge of rural areas. The enlisted men freed leaders of the opposition People's Progress Party, who were jailed after the called March 7 for President Tolbert's resignation. The freed leaders were present at the mansion, but informed sources said they appeared to be acting only in an advisory role.

There was some looting in the capital, much of it by soldiers, with stores owned by Lebanese and Indian merchants and homes of Government officials among the major targets. But the looting was not as widespread as an outbreak last year during rioting over an increase in rice prices. shooting was hears in the capital for hours after the coup, but it apparently came mostly from soldiers firing into the air in celebration. Soldiers commandeered vehicles and rode them through the city. Sergeant Doe proclaimed the situation "under control", but he ordered a dusk-to-dawn curfew and suspended flights to and from the country. He also bradcast order to officials of the deposed Government to report to the executive mansion. The announcements were interspersed with American rock music and African songs.

The 66-year-old slain President was a descendant of freed American slaves who founded the republic in 1847. Though only 5 percent of the population, these "freed-men" have long dominated politics ans commerce, and American cultural influence is evident. Little in known of Sergeant Doe's background, but he is apparently of indigenous origin. "We know nothing about the political views of Sergeant Doe", said the British vice consul, Jeremy Lardner. "we never heard of him before." According to informed sources, however, his political outlook is "moderate".

During the afternoon, the American charge d'Affairs, Julian Walker, met at the executive mansion with Sergeant Doe and invited the Soviet Ambassador to a meeting. The American Ambassador, Robert P Smith, is in the United Stated for medical treatment. Details of the talks were not disclosed but Sergeant Doe appealed to foreign governments over radio not to "interfere". Diplomats here said the coup took them by surprise. Liberia had been regarded as one of Africa's most stable countries. "There was no intimation a coup would take place", Mr Laudner said. "Although one knows such a thing always is possible there was no forewarning".

Mt Tolbert, who was chairman of the Organisation of African Unity, had been President since July 1971 when he succeeded William VS Tubman, who died after almost 28 yers in office. Mr Tolbert was elected to an eight-year term in 1975 and woul have left office in 1983 under a Constitution that limits a president to ine full term. His family has widespread business interests and there have been periodic allegations of conflict of interest and corruption involving Government officials.

The People's Progress Party, which was formed in January, was banned last month after it organised a demonstation at the executive mansion calling for Mr. Tolbert's resignation and a share in political power.

The coup came three days after Amnesty International, a human rights group based in London, charged that the Government had issued "an open invitation to political murder" by offering rewards of $1 500 to $2 000 for the return "dead of alive" of 20 members of the party. The group said in a report: "The 20 proscribed individuals are being sought in connection with a current crackdown on the People's Progressive Party, the first opposition party permitted to function in Liberia since the late 1950's."

Source: New York Times

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)